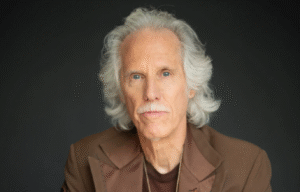

For John Densmore, the legendary drummer for The Doors, the shadow of Jim Morrison has loomed large for decades. Despite being at the epicenter of the counterculture movement with one of the biggest bands in the world, Densmore confesses he lived in “terror” of his iconic frontman. Yet, after Morrison’s untimely death, Densmore would become his fierce protector, battling bandmates and industry giants to safeguard The Doors’ artistic integrity. However, a profound regret lingers: not confronting Morrison about his abusive relationships with women. This complex tapestry of admiration, fear, and enduring loyalty defines Densmore’s unique relationship with one of rock’s most enigmatic figures.

It took John Densmore three years to even visit Jim Morrison’s grave after the singer was found dead in a Paris bathtub in 1971. He didn’t attend the funeral, a stark testament to the strained relationship that had developed. “Did I hate Jim?” Densmore pauses, considering the weighty question. “No. I hated his self-destruction,” he clarifies. “He was a kamikaze who went out at 27 – what can I say?”

Morrison, with his lithe figure, leather trousers, and prophecies of death, sex, and magic, was indeed “spectacularly good at being a rock star.” Hits like “Light My Fire,” “Break on Through,” and “Hello, I Love You” cemented The Doors’ place in music history. Yet, as Densmore readily admits, Morrison was “catastrophically bad at the rest of life.” His alcoholism fueled recklessness, selfishness, and mercurial behavior. Densmore candidly refers to him as “The Dionysian madman,” even a “psychopath,” a “lunatic,” and “the voice that struck terror in me.”

Densmore’s fear wasn’t unfounded. He actively lobbied to get Morrison off the road before his death, even quitting the band at one point in a desperate attempt to halt the destructive spiral. “Some people wanted to keep shovelling coal in the engine and I was like: ‘Wait a minute. So what if we have one less album? Maybe he’ll live?’” he recalls. He questions why he didn’t insist more forcefully at the time, attributing it to a lack of maturity and the prevailing ethos of a different era. “I wasn’t trying to enable him. It was another era,” he explains. Interestingly, his perspective on Morrison’s potential sobriety has evolved. “I used to answer the question: ‘If Jim was around today, would he be clean and sober?’ with a ‘no’. Kamikaze drunk. Now I’ve changed my mind. Of course he would be sober. Why wouldn’t he be? He was smart.”

A Defiant Protector of Artistic Integrity

Now 75, John Densmore stands as a “defiant survivor” of the very music scene he helped forge. This tenacity explains why, in the decades since Morrison’s passing, Densmore has not only chronicled The Doors’ story but has become the fiercest guardian of Morrison’s legacy. His 1990 memoir, a book he says was “written in blood,” might surprise some readers, especially given its later, albeit “dreadful,” adaptation into Oliver Stone’s The Doors biopic. “It took me years to forgive Jim,” Densmore reveals, a testament to the deep emotional scars left by their turbulent collaboration. “And now I miss him so much for his artistry.”

Densmore’s commitment to principle even extended to fierce legal battles against his surviving bandmates. In the early 2000s, he was embroiled in a six-year legal dispute with keyboardist Ray Manzarek (who died in 2013) and guitarist Robby Krieger. Densmore fought to prevent them from touring under The Doors’ name and, more famously, from licensing the band’s music for a Cadillac commercial. “I know. I sued my bandmates – am I CRAZY?!” he exclaims, recognizing the public’s perception. Yet, for Densmore, it wasn’t about the money. “What can I say? Jim’s ghost is behind me all the time,” he asserts. He famously turned down a substantial offer. “My knees were shaking pretty strong when they upped the offer of $5m (£3.8m) to $15m. But my head was saying: Break on Through for a gas-guzzling SUV? No!” Manzarek and Krieger’s lawyers attempted to discredit Densmore, even labeling him a “dangerous communist,” but his unwavering stance prevailed. He won the case, publishing a book about the experience in 2013 and donating the profits to the Occupy movement. For Densmore, “Money is like fertiliser. When spread around, things grow; when it’s hoarded, it stinks.”

A Life Marked by Loss and Reflection

Densmore’s philosophical outlook, shaped by the excesses and losses of the 60s, reveals a pragmatic approach to life and death. He’s “fluent in the language of the 60s elder,” speaking of “peace rainbows” while also displaying a “chilling pragmatism.” He became friends with Tom Petty during his legal battle, and the country music legend’s song “Money Becomes King” resonated deeply with Densmore’s fight for artistic integrity. The loss of Petty, who died after struggles with painkillers, still aches him. “Maybe it’s more noble to die in a friggin’ hospital with a bunch of tubes up your arm… at least you rode the train all the way to the end – you never checked out early.”

Densmore’s own path began in the west LA suburbs, where he was a gifted drummer, starting in high school marching band before discovering jazz and worshipping masters like Coltrane and Davis. He met Morrison at 21, describing him as “tall, bookish and handsome.” They connected through Manzarek at a transcendental meditation workshop, an activity Densmore took up as an alternative to constant acid use, seeking the “separate reality” it offered. He experimented with cocaine in the 70s and 80s but avoided heroin. “Even Jim knew heroin was a serious drug,” he states. “Heroin tried to make you forget everything. It scared me. So I stayed away.”

Compared to his bandmates, Densmore was often the “square.” He admits to moments of jealousy over the attention Morrison received, particularly from women. “Sure, I was jealous. I’d been a teenage drummer with acne.” Yet, his contribution to The Doors’ iconic sound was undeniable, from the shimmying bossa nova in “Break on Through” to the cascading drum break in “LA Woman” that ushers in Morrison’s legendary “MR MOJO RISIN’.”

His personal life also carried immense pain. His brother, also named Jim, struggled with mental illness, eventually dying by suicide at age 27 in 1978 – the same age as Morrison. Densmore later wrote about grappling with suicidal thoughts himself, thinking it might “atone for not saving him.” His sister initially resented him for revealing the “family secret” in his writing, but Densmore found solace in fan letters. “I said: ‘I know it hurts, but I also want you to read these letters I’ve got from fans who say they wanted to commit suicide and didn’t because of this book.’ And that’s why it’s there. Because, as difficult as it is, it’s healing to get this stuff out on the table.”

The Lingering Regret: Abusive Relationships

Densmore’s candid reflections often read like someone recovering from an abusive relationship, such was the terror Morrison instilled in him towards the end. “On the outside, Jim seemed normal,” he wrote, “But he had an aggressiveness toward life and women.” Densmore recalls an early incident where he found Morrison brandishing a knife at a woman. At the time, he did nothing, fearing it would jeopardize the band. “I was really young,” he says now. “I couldn’t figure out whether they were lovers, friends or enemies. I just felt like I needed to get out of there.” Would he act differently today? “Yeah, I would say: ‘What the f*** are you guys doing? Please take it down a few notches here.’”

He also addresses a controversial anecdote from his memoir, which made it into Oliver Stone’s film, regarding Morrison’s partner, Pamela Courson, in the vocal booth during a recording session. “Urgh,” he groans when it’s brought up. “Not so good. I mean, I don’t think he … Well, yeah … See, I’m at a loss for words. SEXIST, what can I say?” When pressed on whether the widely depicted scene actually happened as portrayed, Densmore clarifies: “Well, you know, it didn’t really happen. They were just sort of kissing, and then she left.” He later notes that “Hollywood movies are an impressionistic painting of the truth.” This moment of uncertainty and clarification reveals the messy reality of memory and legacy. “I’m a little nervous that I’ve said stupid things,” he admits later, adding, “But life is messy.”

Densmore continues to embrace life fully. He’s found a new passion in writing, despite his earlier struggles with English in school. “I want to be a writer and I’m voracious for new vocabulary and new ideas,” he shares. “I do sort of feel as if I’m channelling his passion for life… not for life – as I said, he was a kamikaze who went out at 27. But I want to set an example.” This year, he’s set to marry for the fourth time to his partner of 13 years, artist Ildiko Von Somogyi. “I guess I believe in the institution,” he laughs. Densmore’s journey is a powerful testament to resilience. “You want to have a bunch of lives,” he says. “And life does go on – if you stay vital.”