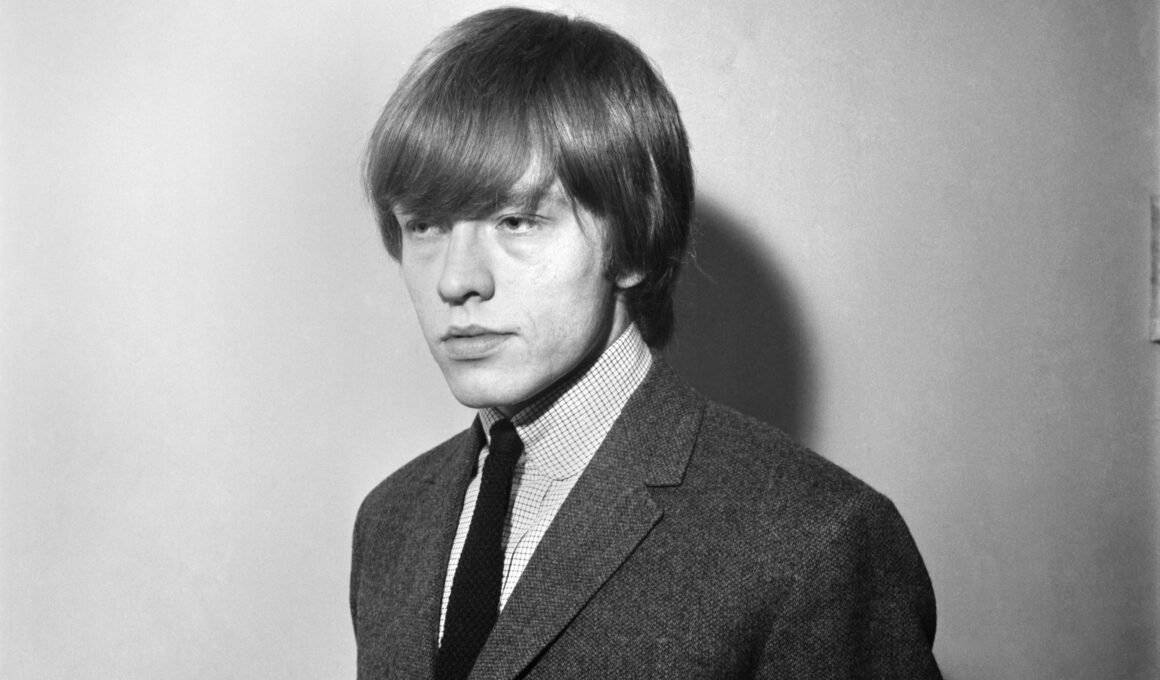

In the vibrant tapestry of rock and roll, few threads are as dazzling and tragic as that of Brian Jones, the visionary who first spun the chaotic genius of The Rolling Stones into existence. His story, a rocket-like ascent to global fame followed by a precipitous crash, has been told countless times. Yet, a new documentary, Nick Broomfield’s The Stones and Brian Jones, offers a profoundly intimate and human re-examination, inviting us to look beyond the legend and into the heart of the man himself.

Broomfield, a master of the documentary form, reveals a surprising personal connection to Jones—a fleeting encounter that left an indelible mark. In 1963, a 14-year-old Broomfield, then a mere schoolboy, found himself sharing a train with a burgeoning rock star. “We were on the same train. I was travelling to school and he was going back to Cheltenham, where he grew up,” Broomfield recounts six decades later. “He was sitting all alone in a first-class compartment. I just tapped on the door and, with some temerity, introduced myself.”

To Broomfield’s teenage astonishment, Jones, then on the cusp of defining a generation with The Rolling Stones, was far from the wild, rebellious icon he was becoming. Instead, he was “warm and charming,” engaging the eager young fan in a surprisingly mundane conversation about trains. “I was surprised at how friendly he was,” Broomfield remembers. “We chatted about trains, mainly. He told me that he loved trains and the line we were travelling on – the Great Western – was his favourite. I just remember thinking how very middle-class, well spoken, polite and accommodating he was.”

This early impression of a well-mannered, articulate musician was consistently echoed in the Stones’ nascent media appearances. Jones effortlessly navigated interviews, projecting an image of quiet charm and intellectual curiosity. Yet, a mere six years after that chance meeting on the Cheltenham train, on July 3, 1969, Brian Jones was discovered lifeless in the swimming pool of his Sussex home, Cotchford Farm. The official verdict: “death by misadventure,” his heart and liver gravely damaged by years of substance abuse.

Beyond the Conspiracy: A Portrait of Vulnerability

While other documentaries have explored various theories surrounding Jones’s death, including a 2019 film that leaned into accusations of foul play, Broomfield’s The Stones and Brian Jones deliberately steps away from such “murder conspiracies.” “I felt they didn’t go anywhere,” he explains, adding, “in terms of the story, I just thought: what’s the point of me wasting a lot of time just to end up dismissing them?”

Instead, Broomfield’s film functions as a profound psychological study of a complex, gifted, yet profoundly insecure individual ill-prepared for the dizzying heights of fame. Through a rich tapestry of first-hand accounts and evocative archive footage, the narrative unfolds slowly, a mesmerizing and often heartbreaking interweaving of astonishing creativity with the inescapable shadows of self-destructiveness and tragedy. Notably, unlike many of his previous works, Broomfield remains unseen on screen, allowing the story to breathe through the voices of those closest to Jones.

“I’ve always wanted to do a film about the 60s, which were my formative period,” Broomfield shares. “That chance meeting with Brian Jones on the train has stayed with me, not least because, back then, he seemed to have everything going for him. He was young, charismatic, incredibly gifted, and an integral part of a group that would define the time more than any other apart from the Beatles. He epitomised that dazzling 60s moment in many ways, which is so very different from now, and then he was suddenly gone. I can still recall the shock I felt on hearing the news of his death.”

The Genesis of a Legend

It’s a fact often overshadowed by the colossal shadows of Jagger and Richards: without Brian Jones, there would simply be no Rolling Stones. He was the architect, the visionary who conceived the band, named them after a Muddy Waters song, and meticulously shaped their early sound, drawing deeply from the American blues masters he idolized. Before they even had a manager, it was Jones who tirelessly cold-called venues across London and beyond, hustling for gigs.

Bill Wyman, the Stones’ former bassist, is unequivocal: “Brian was the leader.” He adds, “Early on, he even signed the management and recording contracts, and, as the most popular member of the band with girls, he received 75% of all Stones fan mail in those early years.” Linda Lawrence, Jones’s girlfriend from 1962 to 1964, further illuminates his early magnetism: “Mick [Jagger] was in awe of Brian. He absolutely loved him. He wanted to be Brian, because Brian had all the girls and all the fan mail.”

Yet, as the 1960s roared on, the angelic-looking, musically prodigious Brian Jones began to unravel. His once pristine blond bob became a disheveled mess, his features bloated by addiction. Fly-on-the-wall footage from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1968 film Sympathy for the Devil starkly captures his decline, showing him too stoned and sleepy to contribute to the Beggars Banquet recording sessions. By June 1969, his self-destructive behavior, coupled with unpredictable mood swings, had become unbearable. With an American tour looming, Jagger, Keith Richards, and Charlie Watts delivered the devastating news: he was out of the band he had founded.

Richards later recounted, “The fact that he was expecting it made it kind of easier, I guess. He wasn’t surprised. I don’t really think he even took it all in. He was already up in the stratosphere.” Abandoned by the group, Jones found himself adrift, “ostracised from his own band,” as music writer David Dalton poignantly observes in the film. Just three and a half weeks later, he was dead.

A Troubled Childhood, A Fated Trajectory

Broomfield’s film meticulously traces the origins of Jones’s deep-seated insecurities to a childhood shaped by the emotionally rigid landscape of postwar Cheltenham. His parents, Lewis, an aeronautical engineer, and Louisa, an organist at the local Baptist church, were upright, strict, and deeply rooted in the bourgeois values of their time. Despite his father being a piano teacher, he vehemently disapproved of his son’s burgeoning obsession with jazz and blues. Wyman recalls how Lewis constantly “badgered Brian to get a ‘proper’ job.”

Pat Andrews, one of Jones’s teenage girlfriends, paints an even bleaker picture: “His mother was very rigid. There was no fun, no laughter. I’m sure she loved him but I think that she didn’t know how.”

Throughout his tragically short life, Jones yearned for, but never truly received, his parents’ approval, even as he defiantly provoked and appalled them with his rebelliousness. By the age of 20, when he formed the Rolling Stones, he had already fathered three children by three different girlfriends and been banished from his parents’ home for bringing shame upon the family. This pattern of behavior, Broomfield suggests, was a direct consequence of his emotionally barren upbringing. “Brian was essentially a helpless child who craved his parents’ approval,” he notes. “After he was thrown out of their house at 17, he would somehow find families that would look after him. Basically, he would charm his girlfriends’ parents and move into their family nest like a cuckoo. Invariably, they would look after him until they found out that he had got their daughter pregnant.”

Love, Betrayal, and the Long Fall

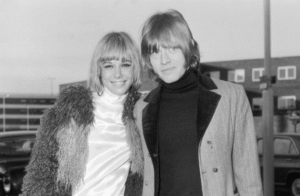

Many of the women who speak in the film, including Andrews and Linda Lawrence, remember Jones with varying degrees of affection and understanding. Lawrence, the mother of his fourth child, Julian, dated Jones during the tumultuous early years of Stones fame. She describes him as “a gentleman – he opened doors and was very gentle spoken.”

However, as the Stones’ fame exploded and Mick Jagger increasingly dominated the spotlight, Jones’s jealousy and insecurity festered. This was compounded by manager Andrew Loog Oldham’s encouragement for Jagger and Richards to develop their own songwriting, sidelining Jones’s creative contributions. “Brian’s confidence suffered as a result,” says Wyman, who speaks at length about Jones’s musical innovations, particularly the audacious embellishments he brought to tracks like “Paint It Black.” “He was a musical genius but he lacked the self-belief to write songs.”

His escalating alienation was exacerbated by his spiraling drug and alcohol use. French pop singer Zouzou, briefly Jones’s girlfriend in 1965, candidly admits to Broomfield, “He was doing so many stupid things all the time. Speed. We didn’t sleep for days on end…”

A pivotal and destructive turning point in Jones’s life was his relationship with Anita Pallenberg, a vibrant German-Italian actor and model, in 1966. Initially, she seemed to reignite his confidence and transformed his self-image, encouraging him to dress with more flair. “There was such erotic power to their pairing, and such glamour,” says Jones’s biographer, Paul Trynka. “He wanted to be seen as a main player in the Stones and she helped that happen.”

Yet, despite its initial glamour, their relationship quickly devolved into a tempestuous and destructive spiral. Film director Volker Schlöndorff, who cast Pallenberg in his 1967 film Degree of Murder, recalls their explosive dynamic: “It was not a tender relationship. They were crazed out.” As Jones’s addictions consumed him, Pallenberg eventually walked away, famously becoming romantically involved with Keith Richards during a trip to Morocco in March 1967. This casual act of betrayal, as Richards later acknowledged, was “the final nail in the coffin” of their already fragile friendship.

The depth of Jones’s despair was so profound that even his parents, shocked by his physical and mental deterioration, finally offered to help him. In one of the film’s most moving passages, a recording of Lewis Jones speaks about that painful time: “What I firmly believed was the turning point in Brian’s life,” he says, “was when he lost the only girl he really loved. In our opinion, he was never the same again… he became a quiet, morose and inward-looking man.”

A Final, Painful Farewell

1967 was indeed a “painful year” for the Stones. Following a tabloid-orchestrated campaign, Jagger and Richards faced drug charges. Jones himself was arrested for possession after a police raid on his London flat. Upon his release, he sent a poignant telegram to his parents: “Don’t judge me too harshly. Don’t think badly of me.”

Jones’s final public appearance with the group was at the filming of the carnivalesque extravaganza, The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, in December 1968. By the time they performed, he was too intoxicated to play properly. “He was just gone,” Jagger later said of his bandmate’s decline, “and not in any condition to do anything. We had to baby him.”

Marianne Faithfull, observing Jones’s isolation and humiliation, presciently articulated what many contemporary viewers might feel: “I saw him as another person with incredibly low self-esteem, who needed help, not to be destroyed and ground underfoot.”

Tragically, the cutthroat world of 1960s rock did not offer such empathy. Just two days after his death, The Rolling Stones held a free concert in Hyde Park, a memorial for their deposed leader before a quarter of a million people. Jagger read from Shelley’s poem Adonais, while hundreds of white butterflies were released. Yet, the presence of new guitarist Mick Taylor beside Jagger underscored the brutal reality: the band had already moved on. Only Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts attended Jones’s funeral in Cheltenham. A regretful Watts later reflected, “He got much nicer just before he died. I felt even more sorry for what we did to him then. We took his one thing away, which was being in a band.”

The Child Within: An Enduring Elegy

Broomfield’s film serves as a powerful elegy for an era and for its first tragic rock and roll casualty. It opens with slow-motion monochrome footage of a young Brian Jones onstage, beatific in the spotlight. Playing over it is an extract from a long-ago interview he gave to a German journalist, where he muses on the inevitable fracturing of the Freudian bond between child and parent.

“A child is a thing to be loved,” he muses in his refined Gloucestershire tones. “A child is the manifestation of both parents and both parents see themselves in the child… he’s a reflection of their own personality. So, one day, when he grows up, he’s going to assert his own personality, which may well differ from the outlook and personality of his parents, who immediately feel upset… They feel they have lost him.”

The film closes with heartbreaking footage of Jones’s parents, looking lost and bereft, at their son’s very public funeral. Over this poignant scene, Linda Lawrence reads from a letter to Jones from his father. It was discovered in a box of letters that had languished in the attic of her family house for 40 years after his death. It reads: “My dear Brian, we have had unhappy times and I have been a very poor and intolerant father in so many ways. You grew up in such a different way than I expected you to. I was quite out of my depth… I don’t suppose you will ever forgive me, but all I ask is for just a little of that affection you once had for me. This is a very private and personal note so don’t trouble to reply. Love, Dad.”

This letter, a belated and perhaps agonizingly insufficient plea for connection, underscores the profound tragedy of Brian Jones’s life: a gifted artist who, despite achieving monumental fame, remained at his core a child craving the love and acceptance that eluded him until the very end. The Stones and Brian Jones invites us not just to mourn a rock star, but to understand the intricate, troubled soul who truly was the beating heart of the Rolling Stones.

Here is the trailer to the documentary.