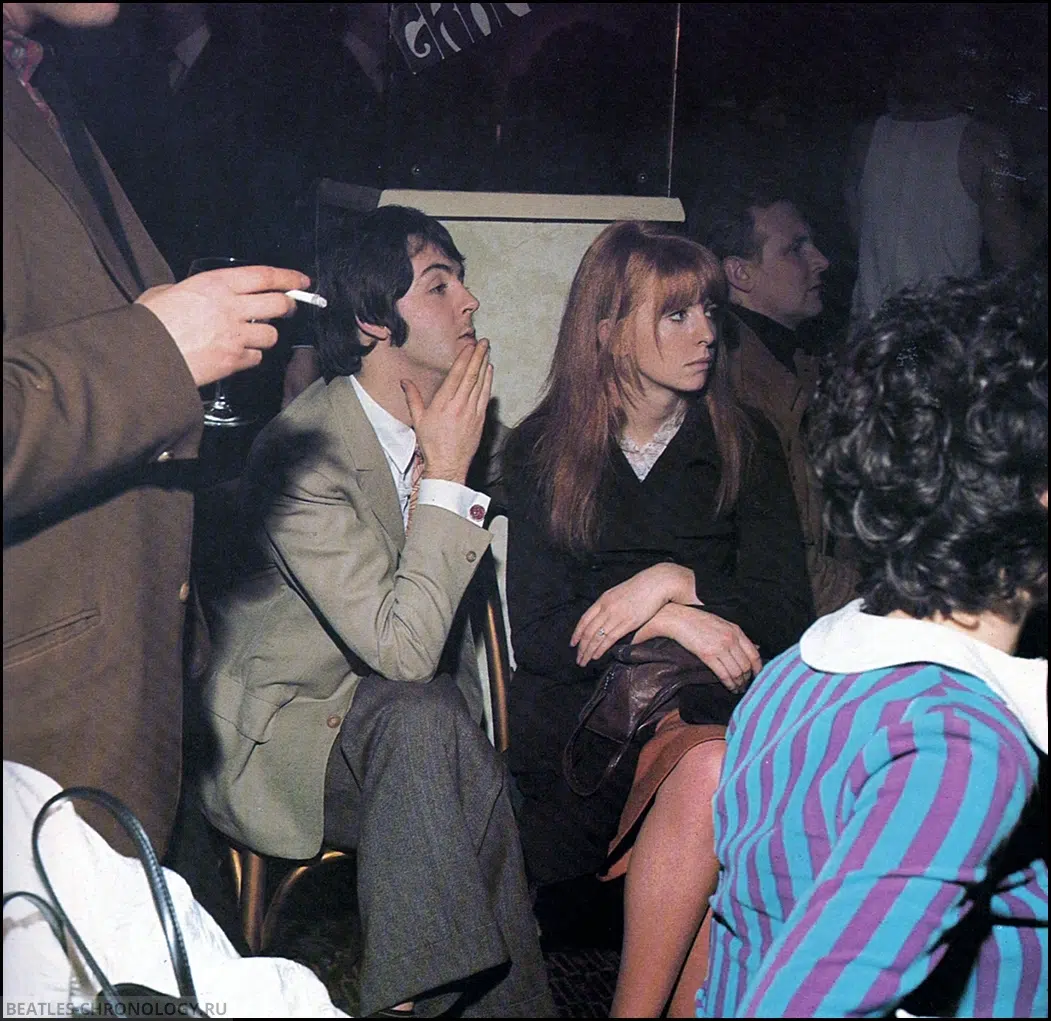

On January 17, 1968, London’s Hanover Grand Hotel became a rare crossroads of pop royalty, creative ambition, and the quiet fractures already forming beneath the surface of the Swinging Sixties. The occasion was a launch party for Apple’s newest signing, the psychedelic pop group Grapefruit, but the gathering quickly transcended the idea of a simple industry celebration. It was, in many ways, a snapshot of a moment when British music still believed it could reinvent itself from the inside out.

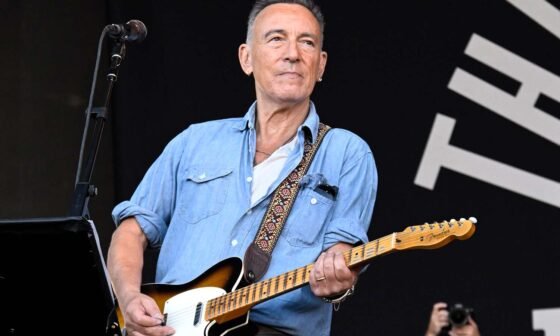

Representing Apple were John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr, arriving together and carrying the public face of a company that promised freedom for artists in an increasingly commercialized industry. Apple Corps, barely months old, had already become more than a label—it was a statement of intent, a utopian experiment built on idealism, generosity, and the belief that creativity could be protected from corporate cynicism.

Notably absent was George Harrison, who at that very moment was thousands of miles away in Bombay, immersed in the recording sessions for his groundbreaking solo project Wonderwall Music. His absence was symbolic as much as logistical. While the others worked to build Apple’s public-facing future, Harrison was already drifting toward a more spiritual, inward path—one that would soon reshape his role within the band.

The guest list reflected the breadth and fragility of the British music scene in early 1968. Brian Jones appeared amid growing concerns about his health and place within the Rolling Stones, his presence both glamorous and haunting. Donovan, a bridge between folk introspection and psychedelic optimism, moved easily through the room, embodying the era’s softer countercultural voice. And Cilla Black, polished and poised, represented the mainstream success that had grown alongside — and sometimes in tension with — the underground revolution.

For Grapefruit, the night carried enormous promise. Personally championed by McCartney, the band symbolized what Apple hoped to achieve: nurturing talent for artistic reasons rather than market formulas. Their sound, drenched in harmony and color, fit perfectly with the label’s early ethos. Yet history would later reveal how difficult it was to sustain that dream amid financial chaos and competing visions.

Accounts from the evening describe a mood that was celebratory but curiously restrained. There was laughter, conversation, and the flash of cameras—but also an undercurrent of transition. The optimism of 1967 had begun to harden into something more complicated. Psychedelia was no longer just playful; it was political, spiritual, and increasingly heavy with expectation.

Looking back, the party now feels less like a beginning and more like a hinge in time. Within months, Apple would struggle under its own ideals, Brian Jones would drift closer to tragedy, and the Beatles themselves would edge toward fragmentation. Yet on that January night, none of that was spoken aloud. What existed instead was possibility—the belief that music could still gather everyone in one room and make the future feel open.

The Hanover Grand Hotel event remains a quietly significant footnote in music history: not because of what was launched, but because of who stood together, briefly, before the paths diverged.